|

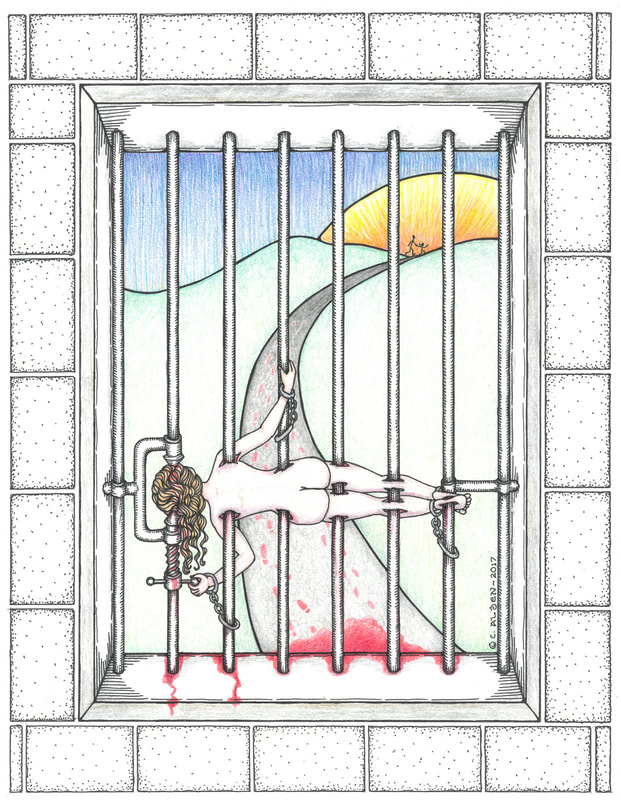

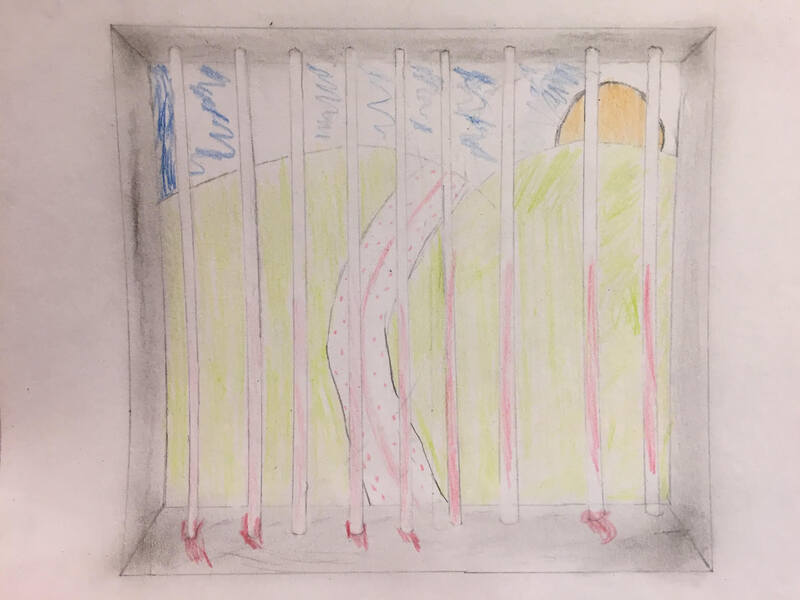

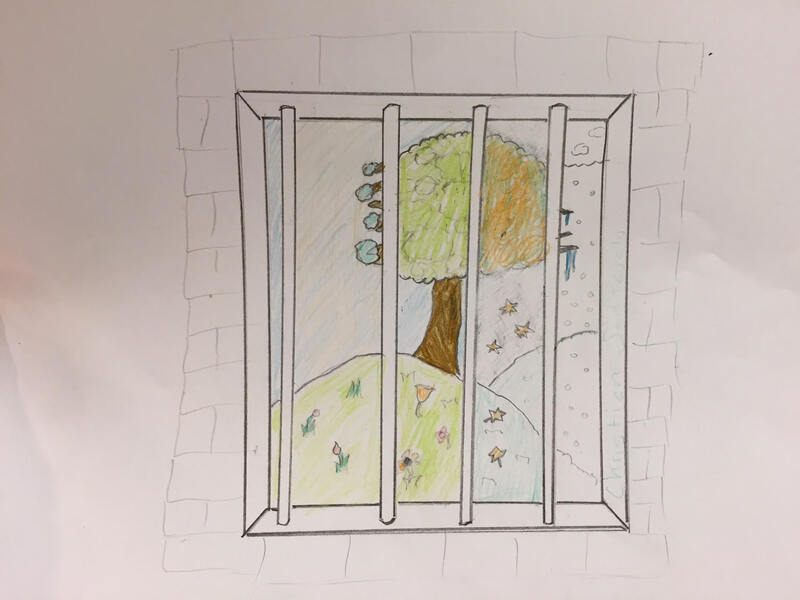

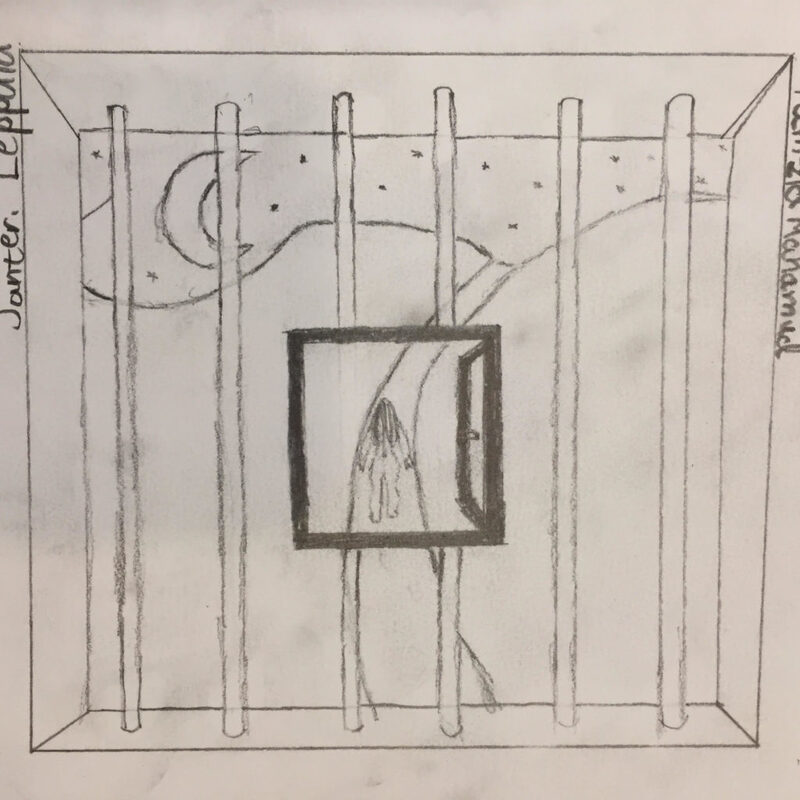

A conversation between Carole Alden and Arlene Tucker was published in Le Journal de Culture & Démocratie in April 2020. Hélène Hiessler translated the article into French from English. Read the publication in French here. Below is the English version. To learn more about Culture & Démocratie, please click here. Free Translation is a multi-disciplinary exhibition showcasing international works generated from an open call to incarcerated people, ex-convicts, and anyone affected by imprisonment. Through this platform, artist and Free Translation co-developer Arlene Tucker met artist, Carole Alden. Through art practice, mail exchange and dialogue ideas, preconceptions, expectations, false realities, and forms of expressions are explored. From the exhibition, Free Translation Sessions were born. In these gatherings we make art, interpretations, and view and discuss artworks received. The sharing of personal stories, experimenting with art techniques, and listening to subjective views can help guide one’s artistic process and shed light on different walks of life. __ Arlene Tucker (AT): The work you contributed to the Free Translation exhibition has been an inspiration for more artworks and the dialogue that has been raised through your pieces has been very powerful. Did you ever think that your work would be a source of translation? Carole Alden (CA): When you create in isolation, you have no concept of your work impacting others. For me it began as a vehicle to turn overwhelming mental and emotional anguish into something survivable. My hope being an evolution from feeling helpless, to a productive plan for my life. In or out of prison, I wanted my life experiences to count for something. I had no idea that a project like Free Translation existed. Where I live, incarcerated persons are essentially shunned. You feel completely disenfranchised from society. There is no real dialogue between incarcerated and free people. Prior to my involvement with Free Translation, l had never seen any effort from free people to understand the experience of being in prison or what might happen in a person’s life to precipitate time spent in prison. You were ostracized and ignored. Made to feel as though you were bankrupt of all that made you human. AT: It was through Wendy Jason at Prison Arts Coalition (now The Justice Arts Coalition) that led us to you and your work. In the end, you made the effort to stay in touch, to share with me. Dialogue is not solitary. CA: Believe me, I am grateful to be found! My mother had found The Justice Arts Coalition and urged me to contact them. I was extremely hesitant after being defrauded by multiple entities claiming to assist incarcerated artists. It was a year of corresponding with Wendy before I decided to take the plunge and trust someone with my artwork again. I was thrilled to find an organization that was true to their word and not in the business of exploiting prison artists. Because of the groundwork of trust she laid, I felt very comfortable in sharing my images with Free Translation when she suggested it. AT: What was this drawing of the Woman Impaled about for you? CA: The first version I had drawn while still in the original jail, awaiting adjudication of my charges. That was towards the end of 2006. I had no access to competent legal representation and no one to advocate on my behalf. I literally felt the system was a continuation of the abuse and death my spouse had planned for me. I felt emotionally and physically stripped of anything that allows a person to feel human. My hopes and dreams were disappearing beyond the horizon. I felt my life draining away and nothing but immobilization and overwhelming anguish and pain. I wanted to die. I felt that if my spirit were no longer tied to a physical body, then it could leave this place to go be with my children. AT: How long were you incarcerated for? CA: I did 13 years out of a 1-15 indeterminate sentence. AT: How did people interact with each other? Was there anybody that you felt you could confide in? CA: The women's prison in Utah had a very different social dynamic than the men’s when it came to certain things. Long term inmates tended to recreate designations that approximated family relationships. Roles were adopted as mothers, fathers, and children. It was not unusual to hear young women speak of having a biological mother, a street mother, and a prison mom. A larger context had to do with commerce, which encompassed drugs, commissary items, and services. In all the time I was down, I kept myself separate from most of what constituted prison culture. I watched, paid attention, and discerned that being enmeshed in the social standards and practices were the primary source of conflict both with each other and the officers. I was determined to remain focused on what I could create in order to be better equipped for the future on the outside. There was really only one other inmate I got close enough to share my hopes and dreams with. She is also an artist and still inside. We were only housed in the same general vicinity for a couple years yet we remain close and invested in each other’s success. AT: What about solidarity or some sort of togetherness within the prisons? Did you feel like you could come together with others or was it very solitary? How were people separated? CA: We saw considerable solidarity on the men’s side. They would organize strikes and protest to get policies changed. This did not happen on the women’s. Too many feared retaliation, or would inadvertently undermine their peers by trying to use relationships with certain guards to change just their own circumstances. Some of it had to do with the feeling that we had more to lose than the men. Tenuous contact with our families was a big deterrent to standing up for yourself. AT: What do you think about the translations, the artworks responding to your original artwork, Woman Impaled? Can you perceive how your painting was translated or interpreted based on their piece of art? CA: Honestly, I was shocked at how perceptive the participants were. They expressed a depth of understanding and empathy I was totally unprepared for. It had the effect of removing my sense of isolation. For the first time in 13 years I felt a restored hope that there was still a place in the world for me. Prior to this, my anxiety surrounding the eventuality of release was debilitating. AT: When you don’t know, you’re in limbo and that can be a hard place to be. Would you like to share on what grounds you were convicted? CA: That limbo of not knowing for sure is probably the most psychologically damaging part of indeterminate sentencing. It robs a person of the ability to create a realistic plan for their future. Everything feels imaginary and moot until you finally have your release date, no matter how close or far off it might be. I had an indeterminate sentence of I to 15 years for second degree manslaughter. My matrix was 5 years. In other words, the suggested time to be served in consideration of mitigating circumstances. I waited 4 years to hear when my date to see the board would be. At a little over 5 years I saw the board. The board chose to ignore the reports of domestic violence and evidence of self defense. I had shot the man as I was cornered in a small laundry room. At that moment. I had no other option that preserved my own life or my children’s. AT: How did you manage to keep making art while incarcerated? CA: Deprivation is the mother of creativity. I continuously scanned my environment for materials to repurpose in order to expand the possibilities of what I could create. Not getting caught was often a large part of the creative equation. Balancing that drive to create with the institutional directive to remain idle was an ongoing conflict. I did my best to fly under the radar and not attract attention. It was an ongoing occurrence for the SWAT team to come through and throw away any artwork, even if you had written permission to construct it. I began with drawing as it seemed to be tolerated more than other forms of expression. During the winter I would utilize the snow as a sculpting medium. At my four year mark, the urge to sculpt overwhelmed my aversion to crochet. I taught myself one basic stitch and began to experiment with yarn as a sculpting medium. As I became more proficient, my efforts evolved from largely meditative to a challenge to keep my thought process sharp. At 8 years down I was transferred to a county facility. With only 70 inmates at a time, the officers took a greater interest in what people did to be productive. They turned out to be far more supportive than any facility I had been in. The last five years have brought multiple opportunities to communicate and exhibit my work. At the beginning of my incarceration I was told by the caseworker that I would never be transferred to a county facility due to my charges and my medical condition. When I was transferred, the receiving caseworker remarked that it was strange as I did not fit the criteria to be housed in a county jail. Aside from medical issues, I still had seven years remaining. County jails are not designed to keep someone for more than a year. Beyond a year, a person’s mental and physical health experiences marked decline. Whatever Utah prisons are lacking, their jails have a fraction of that. You have no access to a yard, usually no contact visits, no education beyond high school, no exercise equipment, or much in the way of jobs, religious options or a library. You basically eat and sleep. Not a place for long term inmates. AT: How was it that you were able to be transferred? Do you feel that because it was a smaller facility, the environment was less volatile? Or does it have anything to do with how those officers were being trained and supervised? CA: Originally I was transferred as a means to disrupt my access to an attorney who had expressed interest in reopening my case. Essentially they moved me in a manner that took away my ability to be in touch with my attorney and separated me from my legal files. Someone did not want my case to be scrutinized and took action to make it impossible for me to continue my appeal at that time. I was separated from all my legal paperwork, contact information, pictures of my children and all my artwork, supplies and personal belongings. Normally they tell you you’re being, “counted out” and you would be permitted time to pack whatever you’re allowed to take, and make arrangements for your family to collect the rest. They sent me to the opposite end of the state and allowed my things to be pilfered by inmates and officers alike. I lost a portfolio of work worth about $75,000.00 that I had hoped to start over with upon release. After reiterating my desire to self harm, they transferred me again to the county jail where I remained for the last 5 1/2 years. I do believe the quality of life in that facility was due largely to the staff and how they chose to treat people. They seemed to be allowed more agency in their personal interpretation of their role as guards. Consequently we had individuals who treated us like human beings and encouraged positive endeavors. This is very rare in Utah Corrections. I am very grateful for the opportunity and encouragement I received in creating my work. AT: How are you feeling since your release? What kind of challenges have you been faced with? In the time you have been free, what have you already adjusted to? CA: Being released, unexpectedly, several years early was a mixed blessing. My over the top elation was tempered by my abject terror over all the things I had no time to prepare for. Would I flinch if a grandchild rushed in for a hug? Would I freeze and bolt if I felt overwhelmed at a Walmart? How on earth would I support myself at the age of 59 with absolutely nothing? The thought of trying to understand fractions of words in texting had me in tears. Thankfully, becoming connected with people in this community has gone a long way in helping me forgive myself for the learning curve I’m tackling. I have had a lot of support in rediscovering that I can still learn whatever I need to and become whoever I choose to be. AT: We cannot do this alone. Amazing that you could emotionally prepare yourself for your release and apply all of that insight into your current situation. When I read your letter about your release that you sent in May, you had talked about this and I was so impressed with your level of emotional awareness. Who were your go to people, your support system? How can we most efficiently and effectively process our emotions? We all are different, but I think sharing tips is one way to show support. At least it is for me! CA: Any release is daunting, but after over a decade, there’s really no way to adequately prepare yourself. Too many intangibles that bombard you at any given time with no warning. I had a couple close friends who had done time over twenty years ago. They were the ones to peel me off the ceiling and encourage me to believe I could do this. I think patience and encouragement are the biggest things. People want to help and tend to be quick to offer up solutions. At that fresh out stage, even having a bunch of problem solving solutions dropped in your lap can leave you feeling overwhelmed and paralyzed with indecision. Be loving and open. Give us the space we need to figure out what we need help with. AT: Now that you are free, what does confinement or imprisonment mean to you? How does that definition differ from prior to your incarceration? CA: Honestly, for most of my life prior to incarceration, I gave it absolutely no thought at all. It had not touched my life through family or friends. It was as disconnected to my reality as if someone said there was a planet of unicorns I could visit one day. About 7 years prior to my incarceration I had a friend go to prison for 11 months on a possession charge. That acquainted me with the gut gnawing fear that family members suffer nonstop during their loved one’s imprisonment. Knowing that they are rarely safe, and without adequate medical care, food or housing. Feeling their spirit and engagement in life wither as days, months, and years pass. In some ways, your family suffers even more. Yet support for your families is scant as well. Social judgment and humiliation is the norm. Being denied the basic dignity of liberty, even if you happen to be somewhere decent, will never be acceptable in my heart. I will never look at a zoo the same way or keeping pets. It hurts to see any living thing denied the choice to live the way they were meant to. ++ Free Translation’s open call for artworks is ongoing and open to all. This exhibition makes use of the translation process as we interact and create new artworks in the gallery space and online. Your works on view will encourage the audience to prompt dialogue, inspire thoughts, and creatively activate the space. Your voice is heard and recognized. Your artistic contribution is very much appreciated. Works can be emailed to [email protected] or mailed to: Free Translation ℅ Pixelache Kaasutehtaankatu 1 00580 Helsinki Finland On the online gallery, under each picture, there is the possibility for you to interpret or comment on that piece. It can be in text, visual, or video format. Your translations and interpretations inspires more thoughts, feelings, and perspectives to be shared and to be sparked. https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org Above are artworks made from a Free Translation workshop with high schoolers from The English School in Helsinki, Finland. These students chose to translate Alden's piece. Prison Outside is centred on the subjects of imprisonment, justice, and the role of the arts in the relationships between people in prisons and people outside. We are interested in perceptions of incarcerated people and ex-convicts in the society, and how we can break the stereotypes and support each other. We focus on artistic practices, be it prisoners’ own initiatives or designed educational projects that promote self-expression, solidarity and communication between people of all walks of life. We also offer a platform for production of artistic projects related to imprisonment, currently with a focus on Finland and Russia.

To keep up to date on Free Translation opportunities, please check www.prisonspace.org. About the authors: Carole Alden was born 1960 in Orleans, France to American parents. Grew up primarily in northern ldaho and Colorado. Dad was a forestry professor and mother a librarian. Nature and self education were the things I was exposed to the most as a child. They continue to guide the majority of my work. I married young and had five children from two marriages that spanned twenty years. I have no formal education nor art training beyond high school. Drawing was something I took up in prison. Prior to that I was a fiber artist with pieces in multiple museum collections. I taught myself to crochet while incarcerated and continue to create a variety of sculptures and wall hangings for venues ranging from political to natural. Arlene Tucker is an artist and educator. Inspired by translation studies, animals and nature, she finds ways to connect and make meaning in our shared environments. Her process-based artistic work creates spaces and situations for exchange, dialogue, and transformations to occur and surprise all players. She is interested in creating projects that open up ideas and that engage the viewer; that invite the viewer to be a part of the narrative or art creation process. In translation, your participation continues to propel the story. Her chapter, Translation is Dialogue: Language in Transit was published in Translating across Sensory and Linguistic Borders: Intersemiotic Journeys between Media (Editors: Campbell, Madeleine, Vidal, Ricarda, 2019). Tucker developed Free Translation with Anastasia Artemeva. Tucker has been collaborating with Prison Outside since 2017 and is author of Translation is Dialogue (2010). www.translationisdialogue.org Comments are closed.

|

ContributorsArlene Tucker: author and curator of TID Arch

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed