|

"The 2023 Aleksanteri Conference will be held on October 25–27 at the University of Helsinki, Finland. This year’s conference will address changes in the relationships within and between the former communist countries of the Global East, by which we mean the region that has been labelled as post/former -Soviet, -socialist, -communist, -imperial. More info about the conference and program here."

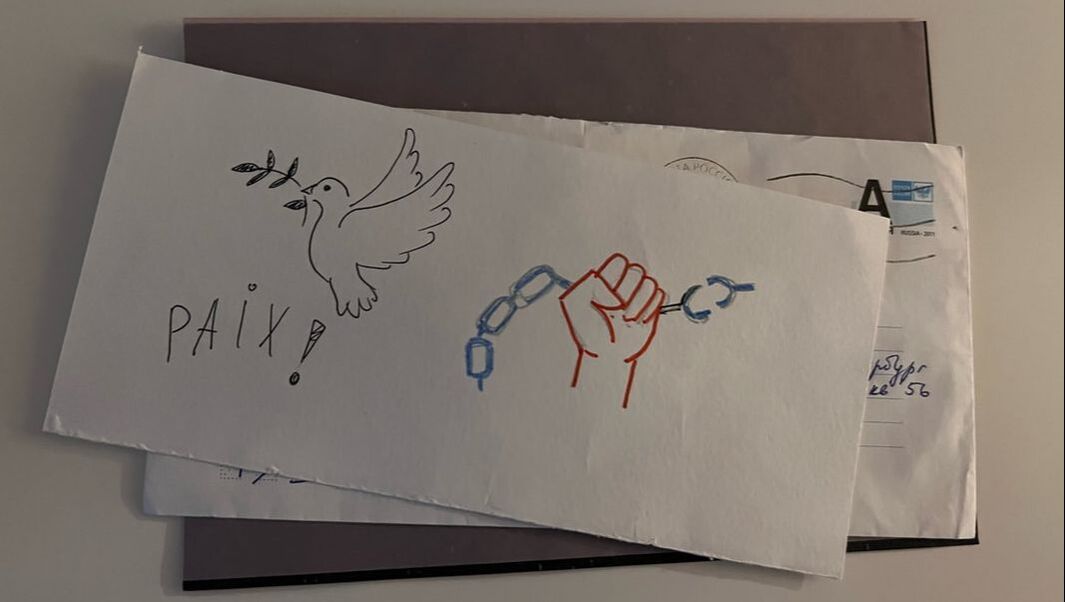

Workshop on Thursday, October 26 from 18:00–19:00 at HALL 4 (B214), Metsätalo Free Translation is a multi-disciplinary project showcasing international works by persons affected by imprisonment. In this project we view works of art and letters received from prisons all over the world. Together we interpret the meaning of the works and create responses based on the translations. These are then sent to the original authors and added to the online exhibition. In this edition the special focus is on political prisoners in Russia. Workshop facilitators Arlene Tucker and Anastasia Artemeva. Institutions Depowered: Schools, Hospitals and Prisons

[Discussion, 150 min] [Audio with captions streamed online] Studio 1, Theatre Academy of Uniarts Helsinki 7 October from 10.00 – 12.30 Birgit Ærenlund Bundesen & Anna Rieder Prison Outside / Free Translation (Anastasia Artemeva & Arlene Tucker) Anissa R. Lewis Eva Koťátková Hosted by Frame Contemporary Art Finland Penal and care Institutions control and reproduce human life throughout its growth, from its birth to the ageing body-mind. Schools, hospitals and prisons are ubiquitous institutions, they directly or indirectly affect a large number of individuals all over the world. Through institutional control and care, individuals and communities learn to recognise behaviour that is not approved and that is considered productive. However, these institutions are also a part of racist, patriarchal and capitalist structures that ban care–as well as direct control–for certain individuals and communities in order to regulate their possibilities to live off common wealth and prosperity. The power of penal, care and educational institutions lies in the reproduction of certain kinds of normalised body-mind and economic orders that benefit the ruling elite. De-powering institutions means to act and live through practices that repair and replace the effects of institutional control and hierarchies within the institution and beyond that. Institutions Depowered: Schools, Hospitals and Prisons presents artistic practices situated within and outside of penal, education and care institutions. The conversation brings together artists, researchers, a psychiatrist and a poet to unpack their practices and collectively explore potential de-powering tactics. Anissa R. Lewis’ practice departs from arts-based women empowerment classes for a Philadelphia County prison’s drug and alcohol abuse unit. She will open up about how these experiences have helped her work to address matters of identity, civic engagement, and neighbourhood relationships in her home town Covington, KY. Artists Anastasia Artemeva and Arlene Tucker have collaborated in the context of the Prison Outside / Free Translation project showcasing international works by currently and formerly incarcerated people as well as anyone affected by imprisonment. They aim to promote self-expression, solidarity and communication between people of all walks of life. Psychiatrist Birgit Ærenlund Bundesen & poet Anna Rieder use poetry to engage clinicians and artists in a constructive dialogue. They are presenting poems from the collection March, March again that will be published by the Danish publishing House Gyldendal in the spring of 2023. Artist Eva Koťátková presents Futuropolis: School of Emancipation which aims to renew the possibilities of education as societal power for the future by bringing together educators, artists and activists to renew the curriculum. Event Schedule 10 Intro and welcome Jussi Koitela 10.10 Presentation by Anissa Lewis + Q&A (20 min) 10.30 Presentation by Anastasia Artemeva & Arlene Tucker + Q&A (20 min) 10.50 short break 10.55 Presentation Birgit Ærenlund Bundesen & Anna Rieder + Q&A (20 min) 11.15 Presentation by Eva Kotatkova + short Q&A (20 min) 11.35 short break 11.45 – 12.30 conversation How to attend This event requires registration using this form. The event takes place at the Theatre Academy of Uniarts Helsinki. An audio stream from the event will be broadcast live on Frame’s website and YouTube channel and available to watch after the event. For the whole programme, click here. See you there!! The 7th IATIS Conference will be held both on site in Barcelona and remotely from 14-17 September 2021. Free Translation is very honored to be a part of IATIS' conference focusing on 'The cultural Ecology of Translation'.

Arlene Tucker will be presenting Making Accessibility: Intersemiotic translation as an inclusive creative practice in working with system impacted artists on September 14th at 15:15 (Room 5/Panel 4). Arlene will share Free Translation's research, practice, and methodology. Tucker has been co-writing an article about these transnational translative experiences with Tomás. Full program and Book of Abstracts available here. If you want to access the online event and have not registered yet, follow this link For entry requirements to Spain, official information can be found here for Spain in General and here for the Autonomous Region of Catalonia. It is advisable to double check details with the Spanish Embassy or Consultate in your country. NOTA BENE: The emails sent by the OC may wrongly land in your spam box. Please check it for updates. The address from which updates are sent is [email protected]. Welcome to Free Translation's workshop on Wednesday, June 9th from 14:00-15:30. The event will take place outside in front of Oodi Library in Helsinki. For more information please click here. Participation is free and open to all!

PIXELACHE HELSINKI FESTIVAL Pixelache is a Transdisciplinary Platform for Emerging Art, Design, Research and Activism, organised by the non-profit association Piknik Frequency ry. It consists of an annual festival in Helsinki, as well as participatory art-science and technology productions, public events, educational programmes, residencies and other activities. Our non-profit association has operated since 2002, also named Pikseliähky. pixelache.ac/pages/about Between 2021-2022, Pixelache will reach its 20th year anniversary, and Pixelache Helsinki Festival is currently one of the longest running cultural festivals in Northern Europe and the Baltic Sea region, that continues to promote emergent inter- and trans-disciplinary practices and thinking between art, design, technology, research and activism. > Pixelache’s 2020-21 Theme: #Burn___ #Burn___ is the thematic premise for the next two years of Pixelache’s cultural output as an association, it connects psychological, social and environmental collapse, and how we can survive it, developing resilience. The programme is designed to give the possibility to different actors to interpret the theme ‘#Burn___’ in multiple ways, and continues our experiments in open and collaborative curation methods. We foresee the focus covering a wide spectrum of possibilities, from the personal to the social and extended systemic perspectives, including for example mental health and ecological states and conditions as related subjects. See you there!! XX a&a

Welcome to join a professional development workshop on how to incorporate artistic practice into a rehabilitation program. We will present the Free Translation project, share our techniques, and discuss ways to participate in the program. We will create a room for us all to share and to hear more about your work. The main language of the meeting will be held in English. Language support in Finnish and in Russian can be given. If you would like to join this meeting and need special technical or communication support, please let us know in your registration form. We strive for an equitable society where art is accessible and dialogue is encouraged.

Meeting via Zoom on: May 12th from 17:00-18:30 EEST May 13th from 10:00-11:30 EEST Free Translation (2017, Helsinki, Finland) is an ongoing international art project and a series of open workshops for system-impacted people to share their thoughts and experience through art practice. In this project we use translation techniques as a means of creatively interpreting works of art. This means that we interpret the meaning of the works and create new works of art based on the translations. This can be a translation into another language or another medium. For example, a poem can be realized into a photograph and a drawing can be written as a letter. In this way, we make new works of art and literature, and attempt to understand each other and ourselves as we have an open dialogue. After a new work is complete, it is sent to the original author via an art exchange program. To date we have received over 100 works of art from people affected by incarceration who have participated in our program. Visit the online gallery at https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org. As a result of many years of collaborating with system-affected people, we recognize the need to prepare a person for the reintegration into society. Free Translation project experts see the idea of reintegration to mean finding a place in society, but also how to communicate, confront, and approach and identify one's feelings, thoughts, and needs. The project offers a diverse, inclusive and transcultural approach to arts in and around institutionalization. Working together with organizations in Finland and abroad we can reach more people who are in need of tools for self-expression. This is a unique project for Finland, as it allows the sharing of art, experience, and knowledge internationally. This project ensures diversity, promotes empathy, and helps to build a more tolerant society. As inclusivity and creating space for all voices to be heard is the project’s aim, we have implemented a way for incarcerated artists to create with others. Our community is a skill-sharing based group for artists, educators, lawyers, policymakers, social workers in Russia, Finland, Belgium, the United States, and beyond. In this cross-disciplinary project we invite workers from different departments, such as social workers, psychologists, guards, and educators. Space is limited and registration is required. The first admitted 15 persons will be able to join. Subsequent registrations will be put on the waiting list. Zoom link will be sent to you the day before the event. Please register here or use the form below. About the authors: Anastasia Artemeva and Arlene Tucker are artists, researchers, educators and diversity agents, who come from the perspective and field of creative expression and process based arts through open dialogue. We are experts in promoting diversity within the creative arts and strive to ensure everyone is included and heard. We have been working extensively with different groups of people of all ages, including youth in children’s homes, currently and formerly incarcerated people, folks in retirement homes, in Finland and abroad. We are honored to be supported by the Arts Promotion Center Finland and Kone Foundation. We can be reached at [email protected]. We look forward to hearing from you. Our best, Anastasia & Arlene  In this picture we are making direct spatial translations of our environment and a text of Tomas' environment. Tomas is a system impacted artist based in the USA. We transcended borders with our translations as we had participants located in the USA, India and Finland. Click here to see the string of interpretations: https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org/?id=detail_600 You are warmly welcomed to join the screening of the short film made collectively during the Trojan Horse Summer School 2020 – Film Making as Spatial Speculation on Friday, October 2nd from 17:00-19:00 (Finnish time). Over the summer I participated in this great event where I camped and created with people on Bengtsår Island in Finland with other participants located in the USA and in India. I was very happy with the random algorithm when picking my video pen friend. Over the course of the week Sachin Yaduvanshi and I exchanged ideas, personal histories and our environments in the most meaningful way despite the miles separated us. One of the main reasons why I wanted to join Trojan Horse was to see how to make filmmaking an inclusive tool. Due to everybody's willingness to experiment and explore and to the great guidance we had from the organisers and mentors, I feel that that was achieved. Thank you for making this possible! The event will take place entirely online on Zoom: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87657835466... Program: 17:00 - 17:10 opening words 17:10 - 18:00 screening of the film 18:00 –19:00 discussion with the participants, mentors, and organisers Trojan Horse summer school 2020 took place on Bengtsår island and online on August 10–16. Five participants and three organizers were camping on the island in southern Finland and six participants and three mentors took part remotely from their homes and studios. During the week we shared time, stories, meals and music. Payal Kapadia, P. Sam Kessie, and Nicole Killian offered exercises for collective filmmaking reflecting the theme “Film Making as Spatial Speculation”. The workshops addressed questions related to island, bodies, memory, and collective practices. We watched films, recorded sounds, wrote body scores, and scripts. We made video letters that together formed a collaborative short film. The videoletters are made by: Shareef Askar, Kate Auman, Jo Hislop, Risto Kujanpää, Christine Yerie Lee, Hanan Mahbouba, Utkarsh Raut, Arlene Tucker, Sachin Yaduvanshi, and Karina Zavidova. The participants’ video letter correspondence - this coalition of short films- will be screened for the first time at the Museum of Impossible Forms in Helsinki on Friday October 2, 2020. You are warmly welcomed to join the screening online via Zoom. Trojan Horse Summer School 2020 - Film Making as Spatial Speculation is supported by SKR Uusimaa. Big thank you to the City of Helsinki for taking care of us in Bengtsår, Aalto University for lending their equipment for the Summer School and Museum of Impossible Forms for hosting us in their virtual and physical space. Trojan Horse is an autonomous educational platform (1) based in Helsinki. Trojan Horse organizes summer schools (2), live action role-plays, workshops and reading circles in the landscapes of architecture, design and art. Trojan Horse aims to create flexible yet steady structures that support critical discourses over a longer time span while remaining open for cross-pollinations and changes. Trojan Horse encourages designers and architects to do more experimental projects, research-based work and form bolder political statements (3).

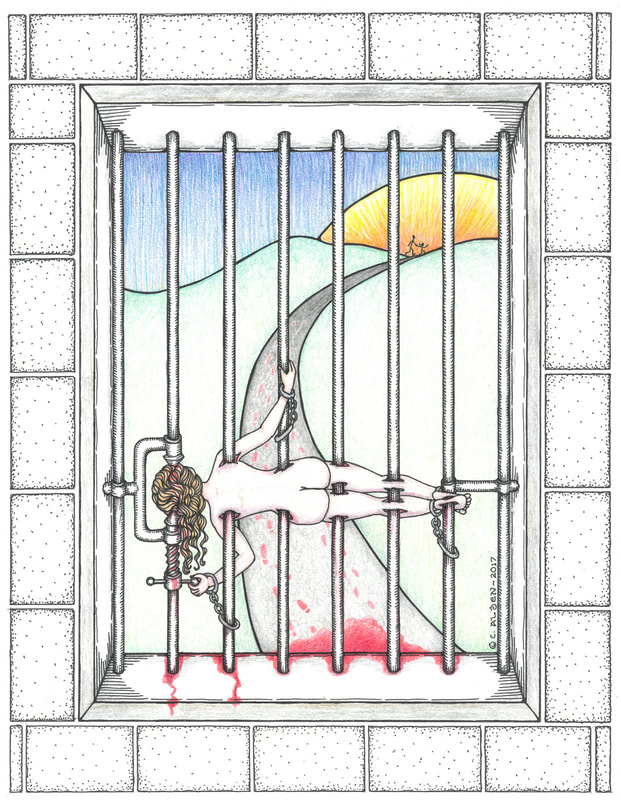

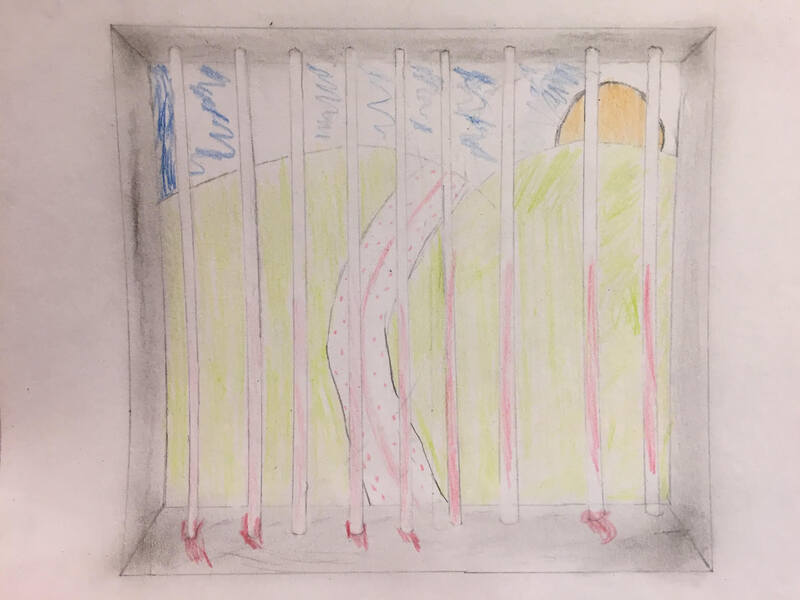

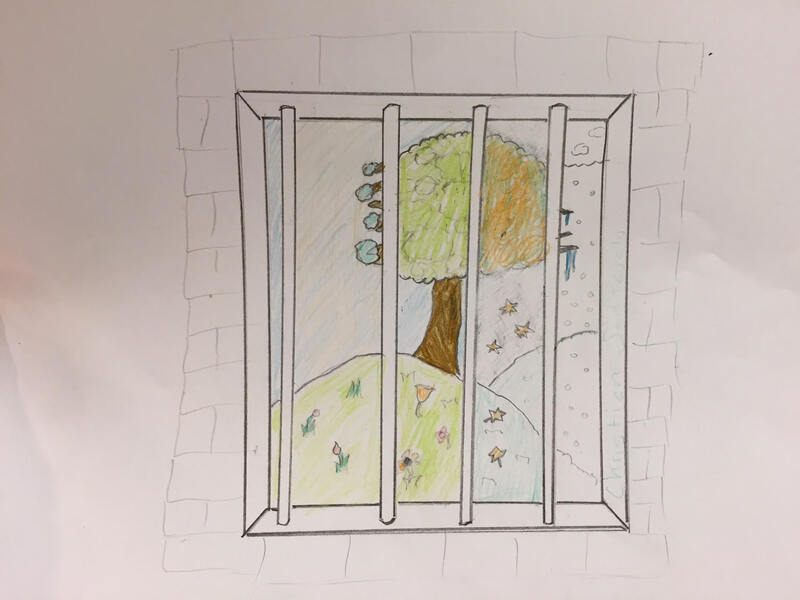

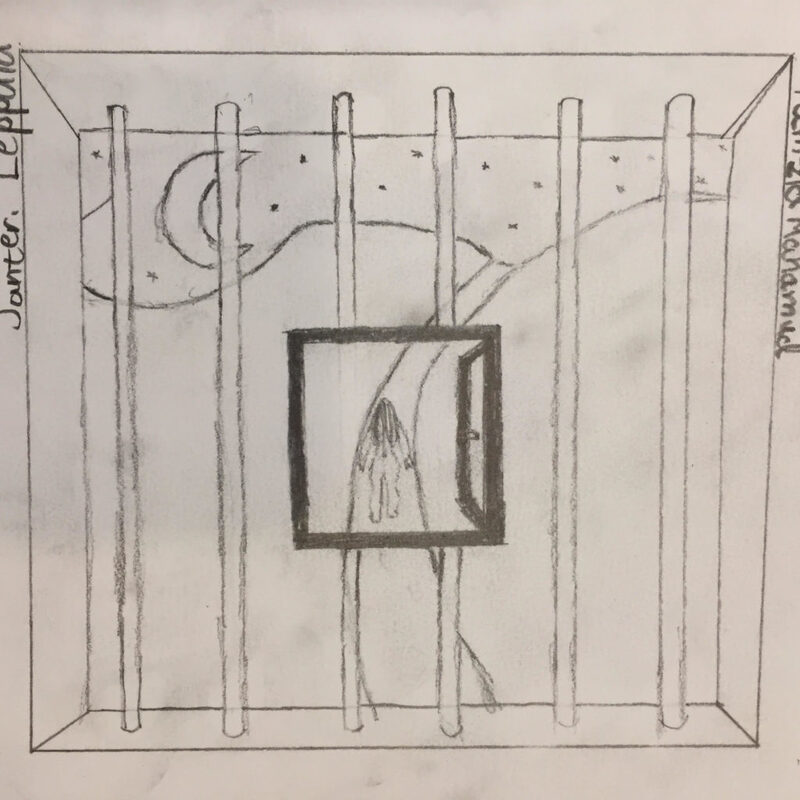

Trojan Horse is currently organized by a group of six people in collaboration with its participants. The content of the events is a result of a collective effort, shared between the facilitators, participants, and everyone whose work supports our gatherings. As any collective or experimental endeavor, Trojan Horse still requires time, thought and effort to develop. Its identity is hybrid and under constant formation. https://trojanhorse.fi --- Museum of Impossible Forms is a cultural space, located in Kontula, Helsinki. It is a contested Space and it represents a contact zone, a space of unlearning, formulating identity constructs, norm-critical consciousness and critical thinking. Impossible Forms are those that erase and facilitate the process of transgressing the boundaries/borders between art, politics, practice, theory, the artist and the spectator. For 2019-2020, Museum of Impossible Forms operates under the curatorial theme of ‘The Atlas of Lost Beliefs (For Insurgents, Citizens and Untitled Bodies)’. Museum of Impossible Forms is a Safer Space. We follow a Safer Space policy to create a welcoming, inclusive, awesome environment. Events at the Museum of Impossible Forms are completely free and accessible without prior booking. https://www.museumofimpossibleforms.org/ A conversation between Carole Alden and Arlene Tucker was published in Le Journal de Culture & Démocratie in April 2020. Hélène Hiessler translated the article into French from English. Read the publication in French here. Below is the English version. To learn more about Culture & Démocratie, please click here. Free Translation is a multi-disciplinary exhibition showcasing international works generated from an open call to incarcerated people, ex-convicts, and anyone affected by imprisonment. Through this platform, artist and Free Translation co-developer Arlene Tucker met artist, Carole Alden. Through art practice, mail exchange and dialogue ideas, preconceptions, expectations, false realities, and forms of expressions are explored. From the exhibition, Free Translation Sessions were born. In these gatherings we make art, interpretations, and view and discuss artworks received. The sharing of personal stories, experimenting with art techniques, and listening to subjective views can help guide one’s artistic process and shed light on different walks of life. __ Arlene Tucker (AT): The work you contributed to the Free Translation exhibition has been an inspiration for more artworks and the dialogue that has been raised through your pieces has been very powerful. Did you ever think that your work would be a source of translation? Carole Alden (CA): When you create in isolation, you have no concept of your work impacting others. For me it began as a vehicle to turn overwhelming mental and emotional anguish into something survivable. My hope being an evolution from feeling helpless, to a productive plan for my life. In or out of prison, I wanted my life experiences to count for something. I had no idea that a project like Free Translation existed. Where I live, incarcerated persons are essentially shunned. You feel completely disenfranchised from society. There is no real dialogue between incarcerated and free people. Prior to my involvement with Free Translation, l had never seen any effort from free people to understand the experience of being in prison or what might happen in a person’s life to precipitate time spent in prison. You were ostracized and ignored. Made to feel as though you were bankrupt of all that made you human. AT: It was through Wendy Jason at Prison Arts Coalition (now The Justice Arts Coalition) that led us to you and your work. In the end, you made the effort to stay in touch, to share with me. Dialogue is not solitary. CA: Believe me, I am grateful to be found! My mother had found The Justice Arts Coalition and urged me to contact them. I was extremely hesitant after being defrauded by multiple entities claiming to assist incarcerated artists. It was a year of corresponding with Wendy before I decided to take the plunge and trust someone with my artwork again. I was thrilled to find an organization that was true to their word and not in the business of exploiting prison artists. Because of the groundwork of trust she laid, I felt very comfortable in sharing my images with Free Translation when she suggested it. AT: What was this drawing of the Woman Impaled about for you? CA: The first version I had drawn while still in the original jail, awaiting adjudication of my charges. That was towards the end of 2006. I had no access to competent legal representation and no one to advocate on my behalf. I literally felt the system was a continuation of the abuse and death my spouse had planned for me. I felt emotionally and physically stripped of anything that allows a person to feel human. My hopes and dreams were disappearing beyond the horizon. I felt my life draining away and nothing but immobilization and overwhelming anguish and pain. I wanted to die. I felt that if my spirit were no longer tied to a physical body, then it could leave this place to go be with my children. AT: How long were you incarcerated for? CA: I did 13 years out of a 1-15 indeterminate sentence. AT: How did people interact with each other? Was there anybody that you felt you could confide in? CA: The women's prison in Utah had a very different social dynamic than the men’s when it came to certain things. Long term inmates tended to recreate designations that approximated family relationships. Roles were adopted as mothers, fathers, and children. It was not unusual to hear young women speak of having a biological mother, a street mother, and a prison mom. A larger context had to do with commerce, which encompassed drugs, commissary items, and services. In all the time I was down, I kept myself separate from most of what constituted prison culture. I watched, paid attention, and discerned that being enmeshed in the social standards and practices were the primary source of conflict both with each other and the officers. I was determined to remain focused on what I could create in order to be better equipped for the future on the outside. There was really only one other inmate I got close enough to share my hopes and dreams with. She is also an artist and still inside. We were only housed in the same general vicinity for a couple years yet we remain close and invested in each other’s success. AT: What about solidarity or some sort of togetherness within the prisons? Did you feel like you could come together with others or was it very solitary? How were people separated? CA: We saw considerable solidarity on the men’s side. They would organize strikes and protest to get policies changed. This did not happen on the women’s. Too many feared retaliation, or would inadvertently undermine their peers by trying to use relationships with certain guards to change just their own circumstances. Some of it had to do with the feeling that we had more to lose than the men. Tenuous contact with our families was a big deterrent to standing up for yourself. AT: What do you think about the translations, the artworks responding to your original artwork, Woman Impaled? Can you perceive how your painting was translated or interpreted based on their piece of art? CA: Honestly, I was shocked at how perceptive the participants were. They expressed a depth of understanding and empathy I was totally unprepared for. It had the effect of removing my sense of isolation. For the first time in 13 years I felt a restored hope that there was still a place in the world for me. Prior to this, my anxiety surrounding the eventuality of release was debilitating. AT: When you don’t know, you’re in limbo and that can be a hard place to be. Would you like to share on what grounds you were convicted? CA: That limbo of not knowing for sure is probably the most psychologically damaging part of indeterminate sentencing. It robs a person of the ability to create a realistic plan for their future. Everything feels imaginary and moot until you finally have your release date, no matter how close or far off it might be. I had an indeterminate sentence of I to 15 years for second degree manslaughter. My matrix was 5 years. In other words, the suggested time to be served in consideration of mitigating circumstances. I waited 4 years to hear when my date to see the board would be. At a little over 5 years I saw the board. The board chose to ignore the reports of domestic violence and evidence of self defense. I had shot the man as I was cornered in a small laundry room. At that moment. I had no other option that preserved my own life or my children’s. AT: How did you manage to keep making art while incarcerated? CA: Deprivation is the mother of creativity. I continuously scanned my environment for materials to repurpose in order to expand the possibilities of what I could create. Not getting caught was often a large part of the creative equation. Balancing that drive to create with the institutional directive to remain idle was an ongoing conflict. I did my best to fly under the radar and not attract attention. It was an ongoing occurrence for the SWAT team to come through and throw away any artwork, even if you had written permission to construct it. I began with drawing as it seemed to be tolerated more than other forms of expression. During the winter I would utilize the snow as a sculpting medium. At my four year mark, the urge to sculpt overwhelmed my aversion to crochet. I taught myself one basic stitch and began to experiment with yarn as a sculpting medium. As I became more proficient, my efforts evolved from largely meditative to a challenge to keep my thought process sharp. At 8 years down I was transferred to a county facility. With only 70 inmates at a time, the officers took a greater interest in what people did to be productive. They turned out to be far more supportive than any facility I had been in. The last five years have brought multiple opportunities to communicate and exhibit my work. At the beginning of my incarceration I was told by the caseworker that I would never be transferred to a county facility due to my charges and my medical condition. When I was transferred, the receiving caseworker remarked that it was strange as I did not fit the criteria to be housed in a county jail. Aside from medical issues, I still had seven years remaining. County jails are not designed to keep someone for more than a year. Beyond a year, a person’s mental and physical health experiences marked decline. Whatever Utah prisons are lacking, their jails have a fraction of that. You have no access to a yard, usually no contact visits, no education beyond high school, no exercise equipment, or much in the way of jobs, religious options or a library. You basically eat and sleep. Not a place for long term inmates. AT: How was it that you were able to be transferred? Do you feel that because it was a smaller facility, the environment was less volatile? Or does it have anything to do with how those officers were being trained and supervised? CA: Originally I was transferred as a means to disrupt my access to an attorney who had expressed interest in reopening my case. Essentially they moved me in a manner that took away my ability to be in touch with my attorney and separated me from my legal files. Someone did not want my case to be scrutinized and took action to make it impossible for me to continue my appeal at that time. I was separated from all my legal paperwork, contact information, pictures of my children and all my artwork, supplies and personal belongings. Normally they tell you you’re being, “counted out” and you would be permitted time to pack whatever you’re allowed to take, and make arrangements for your family to collect the rest. They sent me to the opposite end of the state and allowed my things to be pilfered by inmates and officers alike. I lost a portfolio of work worth about $75,000.00 that I had hoped to start over with upon release. After reiterating my desire to self harm, they transferred me again to the county jail where I remained for the last 5 1/2 years. I do believe the quality of life in that facility was due largely to the staff and how they chose to treat people. They seemed to be allowed more agency in their personal interpretation of their role as guards. Consequently we had individuals who treated us like human beings and encouraged positive endeavors. This is very rare in Utah Corrections. I am very grateful for the opportunity and encouragement I received in creating my work. AT: How are you feeling since your release? What kind of challenges have you been faced with? In the time you have been free, what have you already adjusted to? CA: Being released, unexpectedly, several years early was a mixed blessing. My over the top elation was tempered by my abject terror over all the things I had no time to prepare for. Would I flinch if a grandchild rushed in for a hug? Would I freeze and bolt if I felt overwhelmed at a Walmart? How on earth would I support myself at the age of 59 with absolutely nothing? The thought of trying to understand fractions of words in texting had me in tears. Thankfully, becoming connected with people in this community has gone a long way in helping me forgive myself for the learning curve I’m tackling. I have had a lot of support in rediscovering that I can still learn whatever I need to and become whoever I choose to be. AT: We cannot do this alone. Amazing that you could emotionally prepare yourself for your release and apply all of that insight into your current situation. When I read your letter about your release that you sent in May, you had talked about this and I was so impressed with your level of emotional awareness. Who were your go to people, your support system? How can we most efficiently and effectively process our emotions? We all are different, but I think sharing tips is one way to show support. At least it is for me! CA: Any release is daunting, but after over a decade, there’s really no way to adequately prepare yourself. Too many intangibles that bombard you at any given time with no warning. I had a couple close friends who had done time over twenty years ago. They were the ones to peel me off the ceiling and encourage me to believe I could do this. I think patience and encouragement are the biggest things. People want to help and tend to be quick to offer up solutions. At that fresh out stage, even having a bunch of problem solving solutions dropped in your lap can leave you feeling overwhelmed and paralyzed with indecision. Be loving and open. Give us the space we need to figure out what we need help with. AT: Now that you are free, what does confinement or imprisonment mean to you? How does that definition differ from prior to your incarceration? CA: Honestly, for most of my life prior to incarceration, I gave it absolutely no thought at all. It had not touched my life through family or friends. It was as disconnected to my reality as if someone said there was a planet of unicorns I could visit one day. About 7 years prior to my incarceration I had a friend go to prison for 11 months on a possession charge. That acquainted me with the gut gnawing fear that family members suffer nonstop during their loved one’s imprisonment. Knowing that they are rarely safe, and without adequate medical care, food or housing. Feeling their spirit and engagement in life wither as days, months, and years pass. In some ways, your family suffers even more. Yet support for your families is scant as well. Social judgment and humiliation is the norm. Being denied the basic dignity of liberty, even if you happen to be somewhere decent, will never be acceptable in my heart. I will never look at a zoo the same way or keeping pets. It hurts to see any living thing denied the choice to live the way they were meant to. ++ Free Translation’s open call for artworks is ongoing and open to all. This exhibition makes use of the translation process as we interact and create new artworks in the gallery space and online. Your works on view will encourage the audience to prompt dialogue, inspire thoughts, and creatively activate the space. Your voice is heard and recognized. Your artistic contribution is very much appreciated. Works can be emailed to [email protected] or mailed to: Free Translation ℅ Pixelache Kaasutehtaankatu 1 00580 Helsinki Finland On the online gallery, under each picture, there is the possibility for you to interpret or comment on that piece. It can be in text, visual, or video format. Your translations and interpretations inspires more thoughts, feelings, and perspectives to be shared and to be sparked. https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org Above are artworks made from a Free Translation workshop with high schoolers from The English School in Helsinki, Finland. These students chose to translate Alden's piece. Prison Outside is centred on the subjects of imprisonment, justice, and the role of the arts in the relationships between people in prisons and people outside. We are interested in perceptions of incarcerated people and ex-convicts in the society, and how we can break the stereotypes and support each other. We focus on artistic practices, be it prisoners’ own initiatives or designed educational projects that promote self-expression, solidarity and communication between people of all walks of life. We also offer a platform for production of artistic projects related to imprisonment, currently with a focus on Finland and Russia.

To keep up to date on Free Translation opportunities, please check www.prisonspace.org. About the authors: Carole Alden was born 1960 in Orleans, France to American parents. Grew up primarily in northern ldaho and Colorado. Dad was a forestry professor and mother a librarian. Nature and self education were the things I was exposed to the most as a child. They continue to guide the majority of my work. I married young and had five children from two marriages that spanned twenty years. I have no formal education nor art training beyond high school. Drawing was something I took up in prison. Prior to that I was a fiber artist with pieces in multiple museum collections. I taught myself to crochet while incarcerated and continue to create a variety of sculptures and wall hangings for venues ranging from political to natural. Arlene Tucker is an artist and educator. Inspired by translation studies, animals and nature, she finds ways to connect and make meaning in our shared environments. Her process-based artistic work creates spaces and situations for exchange, dialogue, and transformations to occur and surprise all players. She is interested in creating projects that open up ideas and that engage the viewer; that invite the viewer to be a part of the narrative or art creation process. In translation, your participation continues to propel the story. Her chapter, Translation is Dialogue: Language in Transit was published in Translating across Sensory and Linguistic Borders: Intersemiotic Journeys between Media (Editors: Campbell, Madeleine, Vidal, Ricarda, 2019). Tucker developed Free Translation with Anastasia Artemeva. Tucker has been collaborating with Prison Outside since 2017 and is author of Translation is Dialogue (2010). www.translationisdialogue.org This text is a re-post of Camila Rosa's message first published on Facebook on December 4, 2018 in response to Free Translation exhibition held at MAA-tila in November 2018. The original version and selected responses from Camila's post, written in Portuguese, are below. Last week I went to an art exhibition in Helsinki, made of works of prisoners from several places @FreeTranslation. Overall, the works dealt with the themes of loneliness, fear, longing, depression, time and death. Obvious consequences of confinement time. It got me thinking about how such an exhibition would be important in Brazil, how I would love to take my students there and have following discussions about crime and punishment. Crime in general, even those kinds of crimes that benefit the students, or those socially accepted crimes, that the white majority of the middle class people easily tolerate. But then, I realized that to discuss these issues it's needed to overcome the colonial reasoning / sadistic instinct that wishes the suffering of prisoners. As if all prisoners were murderers and rapists. As if these crimes made the majority of the prison population. As if the crimes of trafficking, selling drugs should only be punished if they involve black and poor people. "Whitened" crimes (violence against women, tax evasion, money laundering - especially in my former home town, Gramado, for example), seem to be more gentle causing greater empathy. I imagine that in a fictional prison setting for crimes like these, associated with white middle / upper classes, overcrowding, police violence, or rape would render greater opposition from society. All that because people do not understand that to be arrested is to be excluded, to be alone, not to have freedom. And that by itself is punishment, and more, an opportunity to reflect and regret. When are we going to end this sadistic spirit that is only happy in the humiliation and in seeing the blood of those who are already fucked? Thank you, Arlene and Anastasia for the initiative and for facilitating this! Response to Camila's post: Letícia - super important the questions you bring. Why not to plan something with the prison population? Especially in prisons for women. Here (in Germany) there's a theater project that works in juvenile prisons that is incredible. I would love to do such a project in the future. Letícia - The situation of women in detention is fucked. Already begins that most often female prisons receive the same budget as male prisons, and women have other needs that men do not have (menstruation, every person with an uterus needs care in those days, needing to be careful with their pussies to not get sick every two weeks, baby care that can be born while a woman is locked up ...). This is not entirely disregarded in prisons for women in Brazil in general. By saying this I do not mean that male prisons are wonderful, but rather they reproduce the patriarchal structure that is extremely cruel to the woman. That's why I think this work in general is important, especially when it's made with women. --- Camila Rosa is a Helsinki-based researcher, educator and performing artist. She is continuously investigating the approximation between art and critical pedagogies, focusing on the intersection of art and public spheres and institutional contexts. As an investigator, she is mostly dedicated to exploring postcolonial epistemology in the framework of performance art. She has been associating multiple art forms in artistic and pedagogical processes in different Brazilian and Finnish contexts. https://camilrosa.wixsite.com/camilarosa Na semana passada eu fui numa exposição em Helsinki, de arte feita por presidiárixs de vários lugares. @FreeTranslation

Num geral as obras tratavam de solidão, medo, saudade, depressão, tempo e morte. Consequências óbvias do tempo de confinamento. Fiquei pensando em como uma exposição assim seria importante no Brasil, em como eu adoria levar alunxs e discutir sobre crime e punição. Crime no geral, até aquele que traz benefícios pra alunxs, ou aqueles crimes socialmente aceitos pela maioria branca das classe médias. Mas logo me veio na cabeça que pra discutir isso tem que superar aquele raciocínio /instinto colonial de sadismo, e de anseio pelo sofrimento ds detentxs. Como se todos presidiários fossem assassinxs e estupradores. Como se esses crimes fizessem a maioria da população prisional. Como se os crimes de tráfico, venda de drogas só devessem ser punidos se envolver negrs e pobrs. Os crimes "branquizados" (violência contra mulheres, sonegação, lavagem de dinheiro - em especial em Gramado por exemplo-), parecem mais delicados e devem causar maior empatia. Imagino que num cenário fictício de uma prisão pra crimes como esses - associados a classes médias/altas brancas - super lotação, violência policial, estupros sofressem maior oposição da sociedade. Porque as pessoas não entendem que estar preso é estar excluídx, ser sozinhx, não ter liberdade. E isso sem si é castigo, e mais, oportunidade pra refletir e arrepender. Quando vamos matar esse espírito sádico que só é feliz na humilhação e no correr de sangue de quem já tá merda? Resposta ao post da Camila: Letícia - super importante teu questionamento. Pq não planejar algo com a população prisional mesmo? Especialmente nos presídios para mulheres. Aqui tem um projeto de teatro que trabalha em presídios juvenis que é incrível. Eu adoraria fazer um projeto assim no futuro. Letícia - A situação de mulheres em situação de reclusão é muito foda. Já começa que na maioria das vezes presídios femininos recebem o mesmo orçamento que presídios masculinos, sendo que mulheres tem outras necessidades que homens não tem (menstruação e que toda pessoa com útero precisa naqueles dias, cuidado com a ppk pra não ficar doente a cada duas semanas, cuidado com bebe que podem nascer enquanto uma mulher está trancafiada...). Isso não é totalmente desconsiderado em presídios para mulheres no Brasil em geral. Com isso não quero dizer que presídios masculinos são uma maravilha, mas sim que a estrutura patriarcal é extremamente cruel com a mulher. Por isso acho importante esse trabalho em geral, ainda mais com mulheres --- Camila Rosa é pesquisadora, educadora e performer vivendo em Helsinque. Ela continuamente investiga a aproximação entre arte e pedagogias críticas, enfoque na intersecção entre arte e o esferas públicas e seus contextos institucionais. Como pesquisadora, ela explora principalmente epistemologias pós-coloniais nas artes performáticas. Ela tem combinado várias linguagens de arte em processos artísticos e pedagógicos, em diferentes contextos no Brasil e na Finlândia. https://camilrosa.wixsite.com/camilarosa Мы приглашаем людей, находящихся в местах лишения свободы, а также бывших заключенных и всех тех, на чью жизнь повлияла тюрьма, принять участие в выставке Свободный перевод. Выставка состоится в ноябре 2018-го года в Хельсинки. Работы будут также представлены в онлайн-галерее.

В течение выставки мы будем создавать новые художественные работы используя “принцип переводчика”. Речь идет о взаимодействии с экспозицией, будь то перевод на другой язык, или ответное произведение искусства, интерпретирующее увиденное. Ваши творчество откроет диалог и активизирует пространство галереи. Выставка организована коллективами проектов Перевод это диалог и Тюрьма Снаружи. Что отправить:

Отправляя нам ваши художественные и литературные работы, вы выражаете согласие на демонстрацию их на выставке в Хельсинки в ноябре 2018-го года, и электронной выставке. Отправляя Ваши работы для участия в выставке, Вы подтверждаете тем самым Ваше авторство на предоставляемые работы и соглашаетесь с тем, что Ваши Материалы могут быть использованы Организатором в целях, связанных с проведением выставки: информированием о программе, различными видами публикаций в СМИ (в т.ч. электронных), использованием в сопутствующей полиграфической продукции. Работы принимаются до 31-го октября 2018-го года. Почтовый адрес: Re: Free Translation c/o Kone Foundation Otavantie 10 00200 Helsinki Finland Фонд Коне любезно предоставил нам свой офис для хранения работ. Размер работ не должен превышать формата A4. Участники выставки несут берут на себя материальные расходы по отправлению работ по почте. Работы не возвращаются. По всем вопросам обращайтесь по адресу [email protected]. Адрес будет объявлен позже. |

ContributorsArlene Tucker: author and curator of TID Arch

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed